This piece is focused on analytics/tech careers and is inspired by two blog posts I refer to often:

- Soft-skills Reading List by Xavier Shay

- The Analytics Hierarchy of Needs by Ryan Foley

Soft skills are often difficult to put into a clear framework and evaluate. They are defined as “personal attributes that enable someone to interact effectively and harmoniously with other people.’ Yet sometimes a skill is valued in one environment and devalued in another (e.g. being blunt). However, difficulty to measure in absolute terms doesn’t make them less important to success. There are definitely different soft skill competencies, because it’s usually pretty clear to see when someone lacks certain soft skills (like tact).

Let’s begin with the end: what do strong soft skills look like? I’m going to define ‘strong’ as ‘good enough to not be a barrier to any individual or group project success.’ That’s it. Strong soft skills mean that projects run smoother and have fewer disruptions, but they don’t always translate to a project’s success. For that, there are a lot of other factors like the broader environment, timing, luck, etc. For example, good writing doesn’t mean a project will get funded, but bad writing will definitely increase a project’s likelihood of not getting funded. Given enough repetitions, however, those with stronger soft skills will start to really stand out. As a side note, getting to a higher level at a company often requires strong soft skills, but also good sponsors in leadership, a highly visible project success, and the desire to climb the corporate ladder (since sometimes you have to do extra work to get full credit for your work) – which not everyone wants to do.

Soft skill gaps, on the other hand, are usually easier to see. In my early career, I had pretty clear soft skill feedback, like ‘stop joking too much at meetings,’ and that I was ‘oversharing technical details’, etc. These gaps can often show up as avoidance as well, such as avoiding leading projects or presentations (due to a fear of public speaking for example). Side note: cool series on progression beyond senior roles.

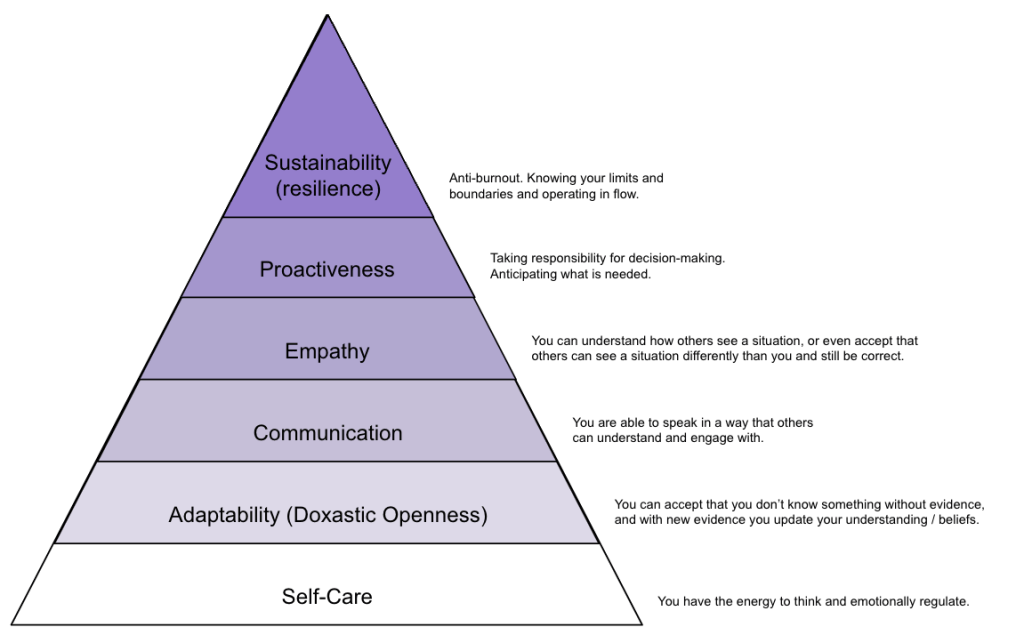

Really, this is about good teamwork. Imagine if you had to run a team, what attributes would you want on your team? And almost as importantly, what attributes would you want to avoid? Let’s get to the hierarchy of soft skill needs:

- Self-care (e.g. you can’t focus if you’re starving). This is the foundation off which other skills are based. I’ll define self-care here as: having resources to think effectively (i.e. you are not in an emotional or health crisis). Basically it’s the actual Maslow’s hierarchy of needs lower levels, in that basic needs are met, so you have the energy to work on a team. No one wants someone on their team who cannot take care of themselves to some degree. Imagine having to count on the work of someone who hasn’t slept for 2 days, is hungover, or just broken up with their partner and wants to talk about it constantly. This can often be overlooked, especially when someone is ‘hustling’ at work. But, for example, someone neglecting their need for emotional intimacy and comfort will usually comes out one way or another. The most common issues I’ve seen recently are (1) isolation during the pandemic – not getting social needs met, and (2) burnout management – not taking adequate time off.

- Adaptability (Doxastic openness). Doxastic openness means: “I am willing to change my beliefs based on a new or better understanding of evidence.” It’s the ability to think critically. We could also call this ‘humility’ or to ‘be curious, not judgmental.’ If someone is unable to change their mind, they will eventually reach a roadblock they will never get past. If you believe something to be true, like ‘I am a perfect programmer’, and someone gives you counter evidence ‘you made a mistake’ – do you deny that evidence to exhaustion, or do you take the information and update your belief: ‘I am a near perfect programmer who made a mistake.’ Baby steps! The alternative is often getting stuck in confirmation bias, where you end up doing a lot more work to arrive at the same conclusion over and over again, regardless of the information presented. It’s hard to influence people if you yourself are unable to be influenced. Side note: this is also a pre-requisite to taking feedback and improving. You cannot improve if you cannot adjust – otherwise you’re just trying your luck over and over. Arguably you could call this the ‘growth mindset’ level, or even just ‘keeping an open mind.’

- Part of why this comes before communication below, is that it is pretty difficult to communicate with someone who is domestically closed, ie they have already made up their mind about everything, which makes communication much less effective.

- Written and Verbal Communication: you can express yourself well. That is, to be able to speak in a way others can understand you. Can you be clear and concise. I’d argue being able to communicate logic is an essential aspect of logic. “If you can’t explain it, you don’t understand it” (The 5 Elements of Effective Thinking by Edward B. Burger and Michael Starbird). A strong communicator is always easier to listen to and work with, and there are a LOT of ways to improve this skill (example video).

- To recap, at this point in the ‘hierarchy of needs’ you have (i) taken care of your basic needs (you ate, you slept), (ii) you are able to receive information and update your beliefs (doxastic openness), and (iii) you are able to express yourself well (communication). These can arguably be done by yourself for the most part – but now we are getting into ‘group projects.’

- Empathy. You can understand how others see the situation, and maybe even identify gaps in their (or your) understanding. You can see situations why you might disagree but both be correct. Without empathy, someone can be highly intelligent and dedicated, yet unable to influence others that much because they do not meet them where there are at – which means they don’t get buy-in. People with low empathy tend to yell at others when something goes wrong, rather than work with them to identify what happened and what to do next time together. In higher forms, I would call practicing deep empathy ‘attunement,’ where for example an empathetic manager will see someone distracted in a meeting, and ask them a question to engage them, or privately check in after and ask ‘is everything okay? you seem distracted.’ They will also be able to recognize when this direct approach is not helpful and adapt to their team’s needs in real time. Another example: knowing how to read the room (e.g. during a presentation or discussion).

- Proactiveness (and ownership). Can you anticipate and plan, instead of just react? This is where you can typically distinguish someone more junior vs someone more senior – an experienced employee will typically plan ahead more and anticipate needs. “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure” (Benjamin Franklin). Chaotic, ambiguous environments CRAVE this kind of proactive leadership. There needs to be someone driving the car with good common sense, not just more passengers. This is where taking responsibility often results in being given more ownership and career progression naturally.

- Sustainability (Resilience). This is anti-burnout. The ability to consistently learn and growth over years and years. This is knowing your limits and boundaries, and getting the important things done consistently. If you can master the previous steps, then it’s just a matter of patience and timing either at your current role or somewhere else you’re more recognized for your strong soft skills. I’m so grateful to my current and former coworkers who provided a source of stability in the team. Someone you can really count on consistently – it helped create a strong, sustainable collaborative team dynamic.

Whew! That’s my list! Or at least the framework I like to use. Now, suppose you identify a gap someone has. The question is: should you help them? Now, often times to progress in their careers, people are asked to coach others. However, for each person there are two major considerations: (1) does this person want to be coached – or at least, are they asking for help/feedback directly or indirectly, and (2) should you be the one to coach them – you can always refer out! There’s no point coaching someone who doesn’t need your help, even if they want it. There’s also no point trying to coach someone who isn’t able to receive coaching – you don’t want to be wasting your time either.

Side note: feedback is about the trust in the relationship, not just the feedback itself. If someone you loathe suggests something to you, it will often have less weight than if it comes from someone your respect.

Let’s get into some coaching examples:

Case A: Self-care and adaptability. An analyst was struggling at work and wondering if she should leave the company. We had a good relationship, and I suggested coaching them formally and they agreed. From our conversations, I believed her real issue was navigating a big re-org, but she also lacked a growth mindset to adapt to the situation. She was scared and overwhelmed, and needed an established ally to rebuild psychological safety (self-care). To help establish myself as an ally, I said we’ll focus on skills that’ll help regardless of whether you stay at the company or not. First thing we did was diagnose the next issue to focus on – just one priority, despite the whirlwind of changes – she needed something stable to work towards. The way I approached this was through talking about my own imposter syndrome, and how one thing that was really helpful for me was to conduct interviews. So I took the full interview set for the position she wanted as a list of general topics to master (i.e. all the interviews data scientists typically have to go through: SQL, Python, data modeling, data investigations, functional partners influence, business acumen). We identified a specific technical gap, and focused on that via biweekly trainings. Over time, a few things happened: (1) she got stronger technically, (2) she started to see how things could improve, (3) things improved. Sometimes just having someone care who isn’t their manager can help someone learn without the fear of being evaluated all the time. Fear drives a lot of stagnation.

Case B. Communication and Empathy. This person was me. I identified a gap / was given feedback that I had to ‘work on my communication’ and I wasn’t sure what to do. I actually ended up going to Cognitive Behavior Therapy (CBT) to work on some non-work interpersonal issues that ended up significantly helping my soft skills at work along the way. The main focus was going through developmental stages to better able to manage my anxiety, which effected my ability to communicate effectively in the workplace (ie I was writing to calm myself down more than to share information effectively). The results have been amazing, but it took a lot of work over the past few years. For example, before therapy, when feeling anxious about a situation, I would often procrastinate by adding complexity to the problem and explaining how massive the ask was – which was more of an emotionally avoidant action than something helpful to the problem. Now, I focus more on ‘did the information land’ to the person I’m speaking with – and try to spend more time fully understanding the situation before diving in a solution, setting expectations, and communicating to others. Something that also helped my writing (and reading comprehension) significantly was reading a lot of books and posting reviews on goodreads – to get more practice synthesizing information from audiobooks I just finished. Toastmasters was also helpful for me in overcoming my own fear of public speaking.

Case C. Proactiveness. This actually comes up a lot and I would say is the majority of coaching I’ve done. Someone is struggling with ambiguity, or how to approach a project, so we talk through how we could do it. For a project, I’ll usually ask: what is the purpose? Who is the audience you’re writing a plan for? If they get stuck, I often say: Imagine you own the business, how could this project add value to your customers / what would you hope someone was working on in this area? This comes with experience and just thinking of ‘what is the thing blocking me’ or ‘what is stopping me from completing this project/step right now?’ Another good one from a college professor of mine: ‘in every problem you cannot solve, there is a smaller problem you cannot solve, find it.’ Talking it through with someone who has proposed/completed a few big projects is very helpful to get to next steps and anticipate potential blockers. If someone struggles finding a project or knowing what to do, I usually ask them go talk through their role, what their team does, and push them towards the analytics community and presentations at the company to see what others are up to.

Case D. Sustainability. A person I worked with was very intelligent, but bad at taking feedback and very sensitive to criticism. Basically they were not very coachable and would be an uphill battle here. I felt like I was walking on eggshells with them, but I saw clear gaps and opportunities to learn and work with them more. I chose not to. They didn’t ask, and I knew it would be very draining for me. I am not responsible for their career or their situation, and I didn’t want to burn myself out. So I let it go, and focused on people who actually wanted to be coached or reached out to me.

Hope some of that was helpful! Obviously hard technical skills are very valuable in a role, but soft skills really help a strong team dynamic form, which is one of my favorite thing to be a part of: a well functioning, effective team. I’m so grateful for all the strong teams I’ve been on!