I don’t have a graduate degree (Masters or PhD) and honestly will likely never get one. Sometimes this can feel like a limiting factor in a technical data scientist role. However, there are ways to fill in some of those gaps to limit this imposter syndrome. Really the main thing is to prevent learned helplessness around a subject where it all seems too complicated (i.e., “Avoidance is the root of anxiety”). No one has complete knowledge of any topic, BUT some folks have anxiety breaking down a dauntingly complex problem and going deeper – THAT is moreso an issue than confidence around all subjects. Not to have a computer science degree, but to be able to think like a computer scientist.

I like to think of the four common data science “academic” gaps I’m going to go into as similar to experience in several adjacent roles:

- Product Manager (PM)

- Machine Learning Engineer (MLE)

- Data Engineer (DE)

- Economist / Economic Consultant

I could probably also add software engineer or even some subject matter experts like financial analyst, psychologist, AI engineer, etc but arguable these could all be bucketed into what I have here in some form. Similarly, some graduate degrees might overlap in the skill sets I’m describing, e.g. Operations Research (statistics/applied math), Bioinformatics (lots of data/statistics), Physics (modeling), Psychology (experimentation), etc. Really these four roles are my 1 to 1 mapping of how I see four masters degrees/specialty areas:

- [PM – MBA] Business acumen for executive alignment, business presentations/soft skills, organization structure, and strategic decision making.

- [MLE – Statistics Masters/PhD] Fundamentals around data, uncertainty, and modeling.

- [DE – CS Masters] Computer science for coding, algorithms, distributed computing, and pipeline infrastructure.

- [Economist – Economics Master/PhD] Causal inference for experimentation and econometrics causality methods (e.g., where experiments are not feasible).

A data science or analytics masters might cover a lot of these subject matters – but it’s hard to beat more in-depth expertise. With these four superpowers I believe I’d be able to add value in almost any data science arena, and, conversely, without knowledge in these subjects something will come up where I feel totally lost. Let’s dig in:

Masters of Business Administration (MBA) or Product Manager (PM) Experience – Decision-Making

If I worked in government, maybe this would be political science or campaign experience. In the private sector, an MBA helps empathize with executive leadership, the people who have to make the big decisions around resourcing, strategic direction, and innovative bets. A mentor of mine said a PMs role, in a word, is ‘influence.’ That is, power to not only make decisions, but make sure they are carried out correctly and the team is clear on the direction the ship is heading. This involves strategic thinking, communicating effectively, and a deep understanding of different people, roles, and incentives.

Here is a great resource of books I’ve read that scratched my lack of MBA itch (along with working with PMs making major product decisions for a few years). People with lots of startup or business/consulting experience tend to be strong here. And actually I’d argue experience in a startup might be more valuable than an MBA (depending on the program/connections and how much of the startup is just putting out fires) by learning in the arena (nothing beats working with a strong mentor here on high priority projects). Because some of this just comes with time, e.g. working with people with business leadership roles and seeing how they think/frame problems. One piece of wisdom that helped me focus here is that some employees get too caught up in using their skills, when value creation for customers is ultimately more important.

While this is not a technical degree, it is distinct from the three others in that it is about ‘what’ projects are worth doing and ‘why’, not ‘how’ to do them well per se. Strategy is specific to the environment, and connecting work to broader efforts. Being able to network, work on group projects, and understand what each business unit does to connect effort to impact. Knowing the market, how businesses are structured, and financial metrics help create somewhat of a map to value (similar to reading a history book to understand how things are structured today) – without it, it’s easy to feel lost when venturing outside a given scope.

Masters of Statistics (MS) or Machine Learning Engineer/Modeler (MLE/M) Experience – Modeling and Uncertainty

Here I specifically am thinking of the statistical components of machine learning (ML) and understanding statistical modeling. There are a lot of resources here online (Andrew Ng coursework, StatsQuest, seeing theory etc) and I highly recommend ChatGPT to review any concepts in depth (e.g., asking ChatGPT: “Give me the code for a basic example,” etc). This is often the core technical work of what people consider to be “data science” – that of creating production machine learning models. The overlap here is often statistics fundamentals and computer science – but I split these two up, as the next few masters degrees are going to have some overlap.

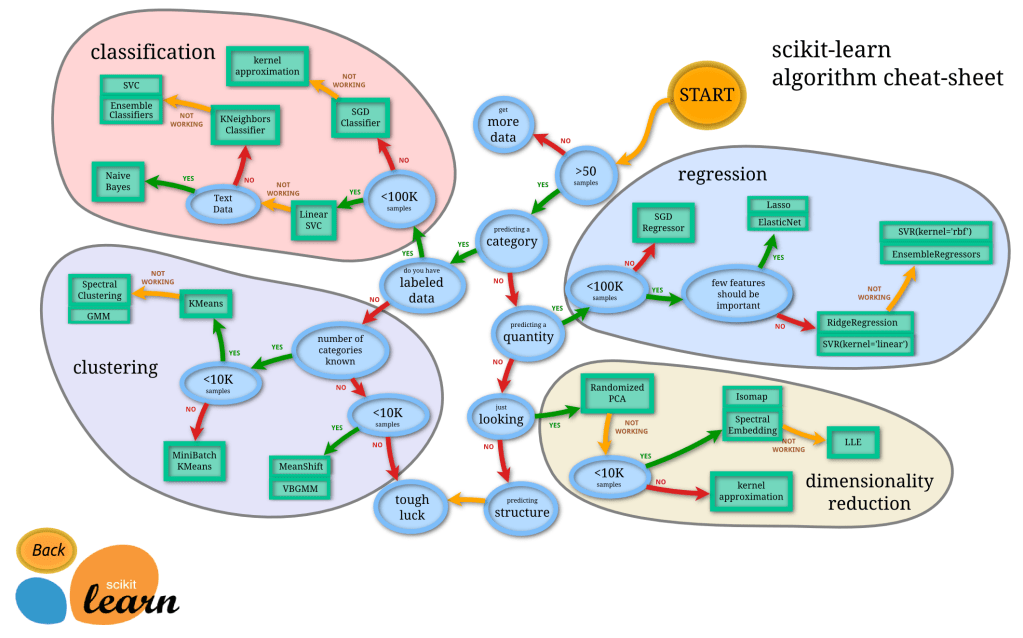

While there are a lot of resources to learn ML, ultimately it is helpful to break down the map into smaller focus areas (see image above) – so that you’ll have the capacity of knowledge to map the right issue to the right problem (e.g., a ranking problem vs a anomaly detection problem vs NLP). While this work can be difficult in coding/implementing in production, what is even more important is understanding where you want to go and the fundamentals of what/how you are optimizing.

I like to think of work problems as having two main categories (1) complex, but easy, and (2) simple, but difficult. Figuring out what to do each day, is complex – but easy (there are a lot of factors, but once you know, you just do it…). Meanwhile, something like a math problem might be difficult, but simple (i.e. there is an answer out there or at least a clearly comparable measurement of success, but it’s hard to get there). Once you have decided on a structure or thing you are optimizing, figuring out and implementing the right ML model is difficult, but simple in the grand scheme of problems in life (e.g., compared to an interpersonal problem at work).

Another added benefit of this graduate degree – which will overlap with Economics below, is that it goes over the fundamentals of statistics, including probability. To fill in this gap for myself, I read some textbooks and wrote a blog post about essential statistics concepts. Some of this just took repetition/volume and work to review and make sure that I could write out the basic concepts on a blank sheet of paper to sharpen a mastery of the basic concepts as a solid foundation to build up into complex models.

Masters of Computer Science or Data Engineering (DE) – Coding

There’s no real replacement for experience with coding (SQL, Python, R, etc). My favorite way to learn these things are to go through exercises (e.g., pgexercises.com for SQL), and technical screens (e.g., leetcode, hackerrank, adventofcode, etc) – although the best confidence builder is interview experience (similar to studying vs taking a test in school). Once the coding/algorithms start to click, the complexity of engineering work and reading code starts to make a bit more sense (e.g., refactoring, debugging, git, automation, etc). Then, later, system design starts to make a bit more sense. Granted, I am not a software engineer and my data engineering is more about making ETLs/Pipelines and less about distributed computing/clustering/partitioning – but knowing some basics makes it easier to understand enough to talk about more complex concepts.

Similar to statistics/math, a lot has been written here, and I would consider this also a ‘difficult, but simple’ concept with lots of online resources (e.g., datacamp, educative.io or this great algorithms coursera course). My go-to wisdom is to try to break down bigger problems into smaller problems of inputs, outputs, and efficiency (i.e., “‘First make it work, then make it work better’”. A strong academic background like a PhD in computer science usually directs folks to software architecture type work (i.e. software developer work) rather than data engineering or ML/AI per se (that might be more of a sub-specialty) – so a masters in CS would be a strong enough background to be able to apply ML/statistics knowledge IMO. Granted, deep computer science work basically becomes math, and deep applied statistics work usually involves some computation. Regardless, in addition to coding, time spent working with engineers (data or software) is incredibly valuable here.

Economics – Causality

I recently added this one to my list mainly because of econometrics (often used interchangeably with ‘causal inference’). Now, the gold standard of causal inference is experimentation (A/B testing), but there are a lot of alternative methods (instrumental variables, regression discontinuity, etc) that add a lot of value in determining causality. This has a LOT of overlap with a statistics degree, often with some slightly different terminology that takes a little getting used to (e.g., thinking of linear regression as “ML”).

IMO The best way to learn causal inference is reviewing case studies and examples, especially around policy research and where there are major decisions like court-rulings. People with economics consulting backgrounds are usually by definition really strong here. How do you decide if private schools offer move value than public schools? You can’t really do an A/B test in practice – and there are major implications, so economists are the people who typically measure the causal impact. Similarly, this comes up in court cases for impact of mergers becoming monopolies, price gouging, etc. There is lots of complexity when you have lawyers arguing different sides and high stakes without a true random experiment to give a more unbiased answer. There are plenty of cases in tech where this skillset can add value to decision-making by determining causality without a randomized controlled experiment (Square blog post on pricing subscriptions, Netflix causal inference blog). This is a specific methodology of economics and typically a part of the econ masters (econometrics/causal inference) rather than a full degree involving a dissertation, which is a specific research project or specialty like macroeconomic forecasting. Some economics overlaps back with an MBA as well, understanding the economy, markets, and decision/game theory where there are sometimes no solutions, only tradeoffs.

Recap

So – if you could have the ultimate data science background, that might include a PhD in statistics and economics, a computer science masters (or PhD in AI), and an MBA while also founding a successful startup. Maybe I should be an Olympic athlete, Broadway performer, and Michelin star chef too just to round it out. The thing is, no one has a perfect background. And even if they did, they also need to apply the right solution/skill to the right problem, which can sometimes be a gamble, similar to listing requirements for a job description. They also have to work with a team, where others might have more specific domain specialties. Everyone’s story is unique, full of strengths and weaknesses. Sometimes people with a strong academic background have to spend a lot of time explaining to non-technical stakeholders why we need to figure out a sample size before we start the experiment rather than just run until we get results. Maybe an ML expert is realizing the space they want to optimize needs basic data infrastructure first. Or maybe you have all the right experiences to be a strong data scientist, but the environment you want to work in doesn’t value it and you cannot get an interview, or maybe you get the job but you cannot convince others to follow along with your ideas.

Ultimately what matters is the ability to learn and adapt; to maintain neuroplasticity and flexibility; to collaborate and work with others on the problems at hand, going in-depth if need be. Even if you had all that knowledge, things change over time, as new technologies and methodologies come out. Data science requires collaboration and soft skills (i.e., “If you want to go fast, go alone. If you want to be far, go together”). Granted, knowledge of the fundamentals make adoption easier – in the same way that learning a second language is easier than learning a first, and learning a third is easier than learning a second, etc. Having a strong academic background can help stay sharp in a particular area – but there are always things we can learn. The important thing is to lean into the discomfort of not understanding why/how something happens and following that curiosity.

Note: a modified version of this blog was posted on the Williams college alumni blog here.