Titan: This town isn’t big enough for two supervillains.

Megamind: Oh, you’re a villain, alright — just not a super one.

Titan: Yeah? What’s the difference?

Megamind: …Presentation!

– Megamind (2010)

Communicating data isn’t just about charts and numbers – it’s about the audience. It took me years to learn how to present information so it lands. Not just to be clear, but so it lands.

My Background on Writing and Presentations

After college, when I started working full time, I’d wrap up a project by writing out everything I did and sharing it. Soon after, I learned to shift from writing what I did to how I came to my conclusions. It was tough to cut out things that were fun or particularly difficult. But I settled for just linking the work in case someone wanted to dig in (a few curious folks likely will, depending on content, regardless of how it’s presented).

Unless you are kicking yourself once a month for throwing something away, you are not throwing enough away.

– Michael Lewis (on Amos Tversky, from The Undoing Project)

I began spending more time cleaning up my steps, removing things that weren’t relevant, and making my process easier to check or reuse. I wanted my work to outlast me, or at least be easy to reproduce after I left. I focused on building a strong data foundation – especially when I made judgment calls about gathering data. I wanted those to be transparent. Looking back, I didn’t always fully understand why I did certain work, but I did learn to tell when it was done poorly.

When I moved into the private sector (SoFi), I started including recommendations at the end of my writing, so my opinion was clear. It felt good to have some ownership and not just analyze from a distance. My goal shifted from being perfectly accurate to making a real-world impact. I still cited my sources and linked my work, but it became part of the appendix, not the core presentation.

At Square, a coworker explained to me that my writing needs to start with a summary at the top that tells the reader what to think and the rest of the time is spent proving it. I began leading with my recommendations and conclusion and let the rest act as a “proof.” A sign I was getting better here was when people challenged my assumptions more than my reasoning. That meant if the premises and logic were sound, the conclusions followed.

Over time my “proofs” got sharper, thanks to good feedback and questions. I started trying to anticipate where people might get confused or disagree, which built more engagement and trust. I also began to think of presentations and documents as just storytelling in different forms with the same goals of connecting with the audience.

I also noticed how people responded differently to different types of evidence. If you say ‘we should go left,’ some people will just go left. Some will ask ‘why should we go left?’ And some people will push back and say ‘we should go right, prove me wrong.’ So I started tailoring my writing of the same information based on different backgrounds. For example, someone new to the company reads differently than someone with years of tenure – I might need to define all my acronyms.

My goal at the start was always to ‘get everyone on the same page.’ The right starting point depends on the audience. If it was a casual or fun talk, I might start with a quote from The Wire. For a business recommendation, I might open with a current challenge or customer story.

Watching the audience helped (when I could) to see if people were engaged / nodding along or had mentally checked out. In a way, I started writing for a distracted version of myself – aiming so someone without context still wouldn’t get too lost.

Disengagement often just means someone got lost. Not because the content was bad, but because the story moved too fast for them to follow or ask a question. So I’d build in recaps at key stages. Sometimes smooth is better than simple. Presentations and documents aren’t just deliverables – they’re dialogues. It’s a pain to get everyone aligned, but it’s better than the alternative. No one wants to sit through 30 minutes of content where it doesn’t click until minute 25. That leads people to feel stupid, or think the presentation was, when neither are true.

If you can’t explain it, you don’t understand it.

– Edward B. Burger and Michael Starbird (The 5 Elements of Effective Thinking)

One unexpected side effect of better communication skills is that I started thinking more deeply about my own premises – like why we even do experimentation, or why we hire data scientists at a company. Also, I may understand the logic behind one decision or project, but what about the organization’s goals overall? How does my work fit in?

I began to think about sharing results while still working on a project, not just at the end. Thinking through how I’d explain something later helped me navigate more ambiguity in the moment. I started to write out plans in advance to leave room for feedback early too. For a product analogy, it’s almost like submitting a minimum viable product for a test run.

I even began choosing projects based on what I would later communicate to an executive or business lead. That shift changed how I perceived the entire business landscape. Not as a pile of work to do, but as a series of problems and bets. Going too deeply into every curiosity was just too expensive in terms of time and resources. If I had to make a choice, and one decision-making framework was to think of how I’d explain it later.

Rewriting is the essence of writing

– William Zinsser (On Writing Well)

I’ll note, to be honest, that sometimes my writing is still bad because I’m tired. It takes work to form an opinion and write clearly. Sometimes I overshare, under-edit, or just don’t do a final recap. Other times I’ve had to lean on reputation or just say ‘I’ll get back to you’ if I’m caught off guard. I’m only human after all. When I started to see writing as its own task, I started treating it like any other work that needs prioritization.

Fear

Wrong is better than vague…. if you’re wrong people will tell you.

– Tanya Reilly (The Staff Engineer’s Path)

A lot of communication challenges aren’t about work or logic – they’re about fear. Fear of being wrong. Fear of having an opinion that aged badly. Fear of failure. Fear of looking dumb or taking up too much space. But humility helps here. Pride and shame are often two sides of the same coin, and both can tie me too tightly to outcomes. Sharing my work lets others correct me, so we both learn. Otherwise the default opinion is usually the gut instinct of the highest paid person in the room.

It is easier to find men who will volunteer to die, than to find those who are willing to endure pain with patience.

– Julius Caesar

One way I’ve worked through some fear is by trying to empathize with executives (i.e. my manager’s manager’s manager, etc). I started to see how much uncertainty they must face. Before I had assumed they knew much more than me. And often they do – especially about the broader landscape. But they are also responsible for many decisions in areas where they don’t live day-to-day. That’s where I can help, as I’m often closest to the data. If someone is responsible for a $30M budget in an area I overlap with, the least I can do is share what I see. If I’m wrong, that’s on me – but I can still share where I stand, grounded in my expertise. In most cases, directionally correct and clearly communicated is better than correct-but-unused insights.

The difference between misconstruing reality and being delusional is the willingness to revise a belief.

– Peter Boghossian (A Manual for Creating Atheists)

Taking up space can feel like stealing it. But I’ve come to believe that group engagement isn’t zero-sum. Yes, time and energy are limited. But attention and curiosity can expand. A one-hour meeting can drag – or it can unlock new thinking. And one good story (or disproved myth) can ripple across a 100+ person org. A bad story might cause some fatigue, but the potential leveraged upside is worth it to share learnings. All focus spent is somewhat of a gamble.

Communicating fully is the opposite of being traumatized.

– Bessel van der Kolk (The Body Keeps the Score)

One time, a really great product manager (PM) lead I was working with (Cynthia Johanson) challenged me on my communication style. I was often over-explaining while trying to transition (briefly) from being a data scientist to a PM. She said to me: ‘Tell me what you want to do, but don’t tell me why.’ The point was, if she had questions, she’d ask. I didn’t need to preemptively justify myself. I never realized how much my need to be understood was getting in the way of actually being effective.

Therapy, self-reflection, and things like Toastmasters (even improv or so I’ve heard) can help immensely here. They let me isolate my fear of being seen, and practice it. Personally, I find it helps to pick one person in the room and talk to them (then maybe switch to another person), not the whole crowd at once. If a speaker messed up a sentence, I wouldn’t care. And neither do most people. That comfort comes with experience.

The secret to gaining access to social connection and social contentment is being less distracted by one’s own psychological business, especially the distortions based on feelings of threat.

– John T. Cacioppo, William Patrick (Loneliness)

I’d argue all communication is communion. Even if you’re writing alone, you’re in conversation. I think about other people as I write like I’m having a conversation. I’m doing it right now. If I am not thinking of someone in particular when I write, I don’t do it.

Ambiguity in Language

Natural languages are the languages people speak, like English, Spanish, and French.… Formal languages are languages that are designed by people for specific applications… [e.g. programming languagee]…. Natural languages are full of ambiguity, which people deal with by using contextual clues and other information. Formal languages are designed to be nearly or completely unambiguous, which means that any program has exactly one meaning, regardless of context…. Because we all grow up speaking natural languages, it is sometimes hard to adjust to formal languages.

– Allen Downey (Think Python).

Why is language so hard? Because ambiguity is often intentional.

A mafioso says, “This is a nice store. It would be a shame if something happened to it.” The goal is pressure without an explicit (illegal) threat. In a formal language, it would be: if money then no burn store else burn store.

A low pressure date request is, “What are you doing later?” It opens the door without explicit rejection risk. In code, that becomes: if interested then date else nevermind I was just curious.

This structure allows people to stay vague and noncommittal. It takes more effort to be clear and direct, which is exactly why clarity is influential.

School

Academics write horribly because they write for an audience that’s out to destroy them. They’re writing not to be understood, they’re writing not to be misunderstood. They’re terrified of being wrong.

– Michael Lewis (exact quote unverified)

Not all academics write poorly – this is a generalization. But it’s worth asking where & how we learned to write. If you have an academic background, check out this Larry McEnerney talk. It’s over an hour and worth every minute. It reframed how I see writing, and academia. Some key points:

- Most people learn writing as students writing for teachers. And those teachers are paid to evaluate how their students think (e.g. why they might ask for definitions first, because it’s easier to correct).

- Writing to think is good, but writing to be read is different.

- Value lies in readers… not in the thing [ideas].

- You think writing is conveying your ideas to your readers, it’s not… It’s changing their ideas.

- So now I don’t say to him, why do you think that? I say now, why should I think that?

- Knowledge isn’t just a pile of facts. It is what today’s power structures define as knowledge (and it’s permeable). It’s not pretty, but it’s true of publishing academic papers as well as in business.

- [On getting a PhD] half their time is spent learning more stuff. The other half is learning their readers.

- ‘Hey readers, I’ve read your stuff. I’ve thought about what you think and I have something to say’ [versus] ‘Hey readers, I’ve read your stuff. I know what you think, but you’re wrong.’ Which one are they gonna pay attention to?

- Do not explain, argue.

In a world of endless content, using the attention we do get well is crucial.

Some Resources and Tips

Book recommendations + some quotes:

- Nonviolent Communication by Marshall B. Rosenberg

- At the core of all anger is a need that is not being fulfilled.

- As we’ve seen, all criticism, attack, insults, and judgments vanish when we focus attention on hearing the feelings and needs behind a message. The more we practice in this way, the more we realize a simple truth: behind all those messages we‘ve allowed ourselves to be intimidated by are just individuals with unmet needs appealing to us to contribute to their well-being. When we receive messages with this awareness, we never feel dehumanized by what others have to say to us.

- Crucial Conversations by Kerry Patterson, Stephen R. Covey, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, Al Switzler

- Respect is like air. As long as it’s present, nobody thinks about it. But if you take it away, it’s all that people can think about. The instant people perceive disrespect in a conversation, the interaction is no longer about the original purpose—it is now about defending dignity.

- Here’s the problem we have to fix: When we find ourselves at an impasse, it’s because we’re asking for one thing and the other person is asking for something else. We think we’ll never find a way out because we equate what we’re asking for with what we actually want. In truth, what we’re asking for is the strategy we’re suggesting to get what we want. We confuse wants or purpose with strategies.

- The Visual Display of Quantitative Information by Edward R. Tufte

- Graphic excellence is that which gives the viewer the greatest number of ideas in the shortest time with the least ink in the smallest space.

- Lie factor = size of effect shown in graphic / size of effect shown in data.

- Graphical elegance is often found in simplicity of design and complexity of data.

My writing has improved immensely not just by reading, but also by writing book reviews on Goodreads. Just by planning for a review I’m practicing thinking about what information I want to take with me (e.g. quotes), and how I might evaluate the book. This is not that dissimilar to looking through data and crafting a useful narrative. Another benefit is I have a quick reference for quotes to use (many of which I used above)!

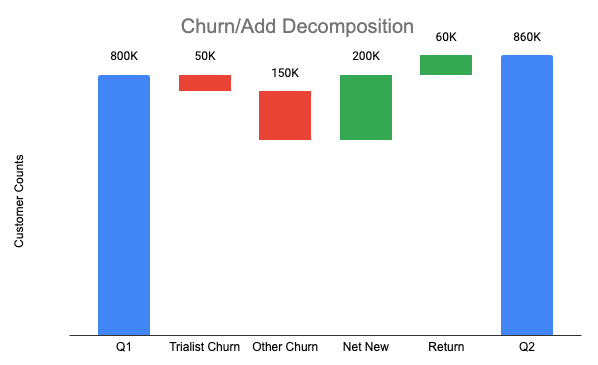

Bonus: here’s one of my favorite visuals in a chart (of change from quarter to quarter). Notice how there’s no grid lines, and the story is very easy to follow from left to right (and by color) on how we went from 800K to 860K customers (fake date obviously), and our quarterly churn and net new customers. There isn’t really any wasted ink.

Conclusion

That’s it. That’s all I wanted to write. Thanks for reading.

Shout out to some former colleagues who helped me communicate better: Xavier Shay, Anne Yeung, Michael Higgins, Edmond Chan, Vibhor Chhabra, Cy Villaflores Shaw, Cynthia Johanson. There are many, many more here – but these are the ones who I thought of while writing.